June 3, 2014 | War On The Rocks

Al – Shabaab Strikes In Djibouti

Co-Authored by Henry Appel

On Saturday evening, May 24, a Somali man and his female companion took their seats in La Chaumière, a restaurant in Djibouti’s capital popular with tourists and Western military personnel. Before even checking the menu, the pair detonated suicide vests hidden under their clothes, killing a Turkish national and wounding eleven international soldiers. Three days later, the al-Qaeda affiliated Somali militant group al-Shabaab claimed credit for the attack, explaining that it “targeted a restaurant frequented predominantly by French Crusaders and their NATO allies from the U.S., Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands.”

This attack is significant for several reasons. First, it is the first suicide bombing in Djibouti’s history, shattering the country’s long stretch of insulation from the many terrorist attacks that have struck its neighbors. Second, Djibouti is an important base of operations for Western forces in the region, including the U.S. Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa. The bombing should be understood in the context of a recent spate of attacks by al-Shabaab, both in Somalia and outside.

Djibouti’s Military Significance

There are two major reasons al-Shabaab wanted to strike inside Djibouti. The first, highlighted in al-Shabaab’s statement, is the Western military presence in the country. The only U.S. military base in the Horn of Africa, Camp Lemonnier, is in Djibouti. Camp Lemmonier is used as “a staging ground for counterterrorism operations in Yemen and Somalia,” and has even been employed as the staging point for drone strikes in Yemen. Lemonnier also serves as a base for training of regional forces, some bound for Somalia as part of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) mission.

The Western military presence is not limited to American forces. France—which was mentioned first in al-Shabaab’s claim of responsibility—also maintains a military base in Djibouti, which is the largest of its three installations in Africa. France’s Djiboutian base helps to support its multiple missions on the continent.

The second reason al-Shabaab has a vendetta against Djibouti is the country’s contribution of troops to the AMISOM force, which is designed to protect and stabilize al-Shabaab’s mortal enemy, the Federal Government of Somalia. As Djibouti prepared to send 960 of its troops to join the AMISOM mission in December of 2011, al-Shabaab spokesman Ali Mohamed Rage warned the Djiboutian people that “if you do not keep them from attacking us, you will see the bodies of your children scattered on Mogadishu streets.”

Al-Shabaab’s Offensive

Al-Shabaab may be seeking to intimidate countries that have committed troops to Somalia, attempting to make them rethink their commitment to the mission. Indeed, the group has loudly explained that its escalation inside Kenya is a sign of things to come. On May 22, senior al-Shabaab commander Fuad Mohamed Khalaf said that “we have transferred the war to inside Nairobi,” and after a series of early May bombings in Kenya that killed more than 35 people, he threatened more suicide attacks. On the same day, senior al-Shabaab commander Fuad Shongole promised that the group would carry its jihad to Kenya, Uganda, “and afterward, with God’s will, to America.”

Al-Shabaab’s strategic modus operandi has recently been to carry out attacks against Somali citizens, the Somali military, and AMISOM forces. In the case of this last target set, the group’s objective is, in part, to send the message that occupying Somalia to support the government is not worth the cost. Attacks in neighboring states further drive home the point, and there is a growing voice in Kenya’s political class in favor of abandoning its Somalia mission. Earlier this month, for example, Kenya’s senate minority leader Moses Wetangula argued that “in our attempt to help a neighbor we have suffered a lot—costs ranging from human loss and monetary loss.” He argued that it was time to “end our presence in Somalia and save the country from further conflicts.” And Ronald Tonui, a member of Kenya’s national assembly, further argued that “it does not make any sense that our forces are trying to keep peace in Somalia at the expense of Kenyans’ safety,” referring specifically to the threat of terrorist attacks. There is, of course, also the risk that attacks like that at the Westgate Mall will increase rather than erode Kenyan resolve. But these public statements from elected officials are significant, and will likely bolster al-Shabaab’s belief that it can reduce the pressure it faces within Somalia’s borders by perpetrating attacks beyond them.

The recent attack in Djibouti serves a similar purpose, but with an eye toward the West.

Conclusion

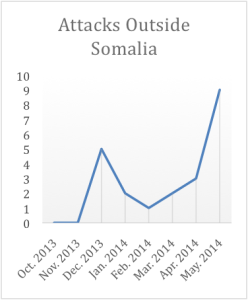

Since October 2012, the vast majority of al-Shabaab’s attacks have struck at Somali or Kenyan targets (84% Somali, 15% Kenyan, <1% Ethiopian). But the group’s frequent bellicose threats and warnings, combined with its status as an official affiliate of al-Qaeda, have kept the question of whether it will strike outside the immediate region prominent. Though this attack represents an escalation on al-Shabaab’s part, the militant group has not shown the ability to carry out a sustained campaign outside of Somalia and Kenya. Its operations are likely to continue to be heavily concentrated in those two countries.